|

||

|

|

|

I’d always thought time travel was impossible.

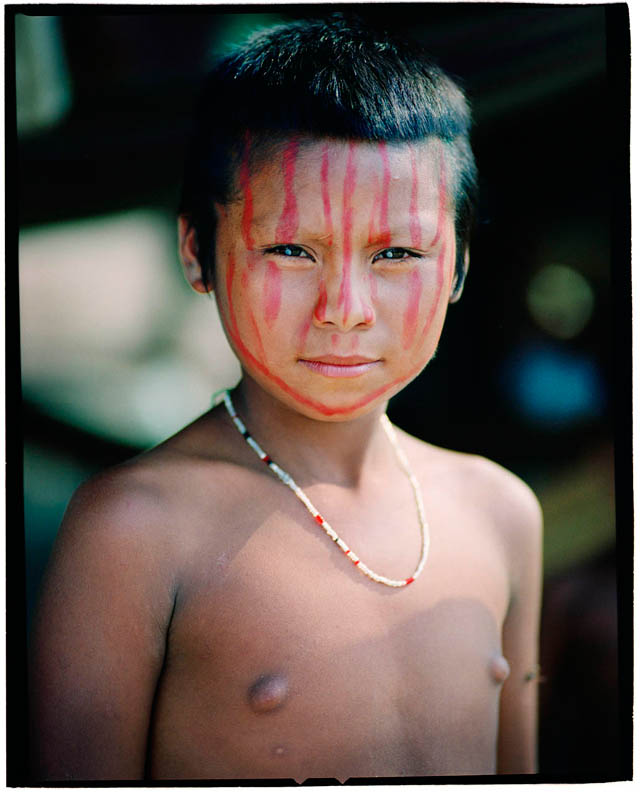

But I’m in Colombia, by far South America’s strangest country. It is the land

of Nobel Prize winning author Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s “One Hundred Years

of Solitude” and Magical

Realism, so just about anything

is possible. Forty minutes after boarding a plane in Bogotá, the nation’s

capital, it turns out I was wrong; suddenly, the clock has been turned back

five hundred years. I’ve landed in San José

de Guaviare, a town bordering on

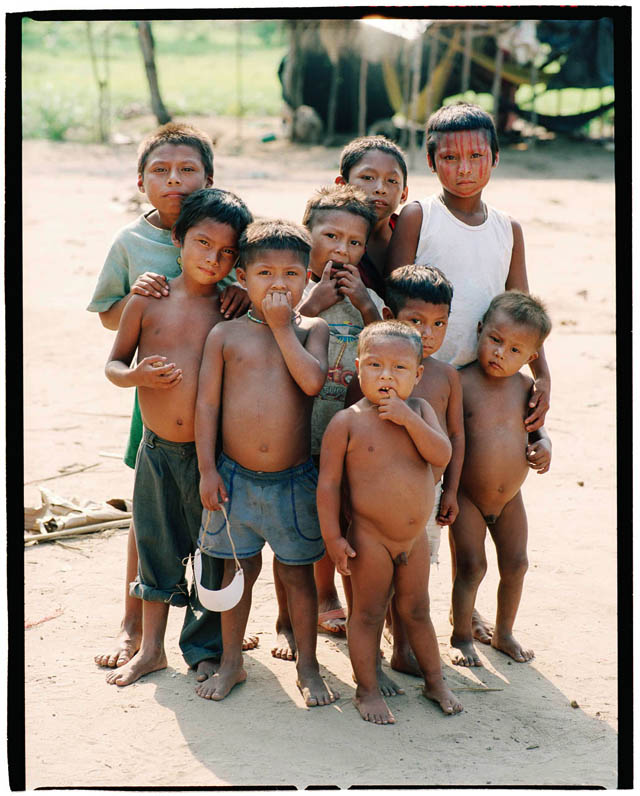

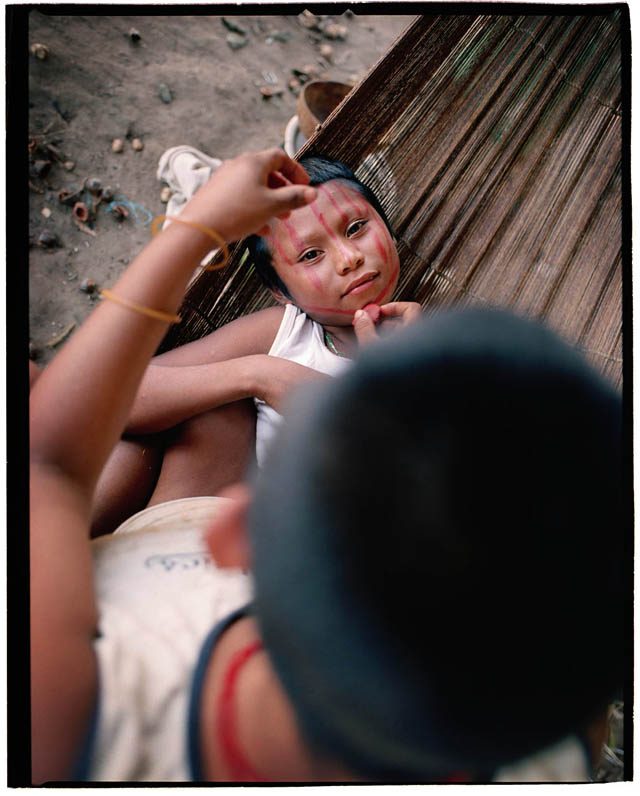

the Amazon Basin. Twenty children’s faces are staring at me in absolute

amazement. They’ve never seen white skin, or blue eyes or anything other than

straight black hair. I stare back, equally amazed by their lack of eyebrows, their

close-cropped hair with triangular bald patches and their faces painted with red

dye, which is used along the Amazon River as mosquito repellant. They

approach cautiously, some touching my skin as though I were a precious jewel.

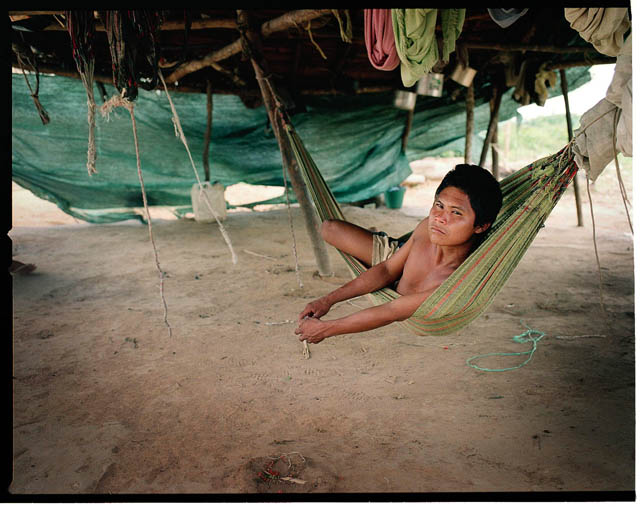

Awoken by the fuss,

several of the elders stir from their hammocks and come over to investigate.

The coffee and rice I offer as a show of good will are accepted graciously,

although I now realize they were unnecessary. This is a very peaceful tribe,

friendly and hospitable, even though, or maybe because, their contact with

“white man” has been extremely limited – until now. Even with the adults,

communication is difficult as few of them speak Spanish. They talk amongst

themselves in a high-pitched chatter, the entire group often laughing in

unison. When I take out my tripod, the group falls silent. The children play

with the tripod for hours afterwards and their amazement does not diminish. Until recently, a meeting

like this would have been impossible; the Nukak Maku were nomads – changing their whereabouts every

couple of days in the extensive rain forests of the Amazon basin. Currently, most

of them are located in refugee camps like the one I am visiting. I arrived

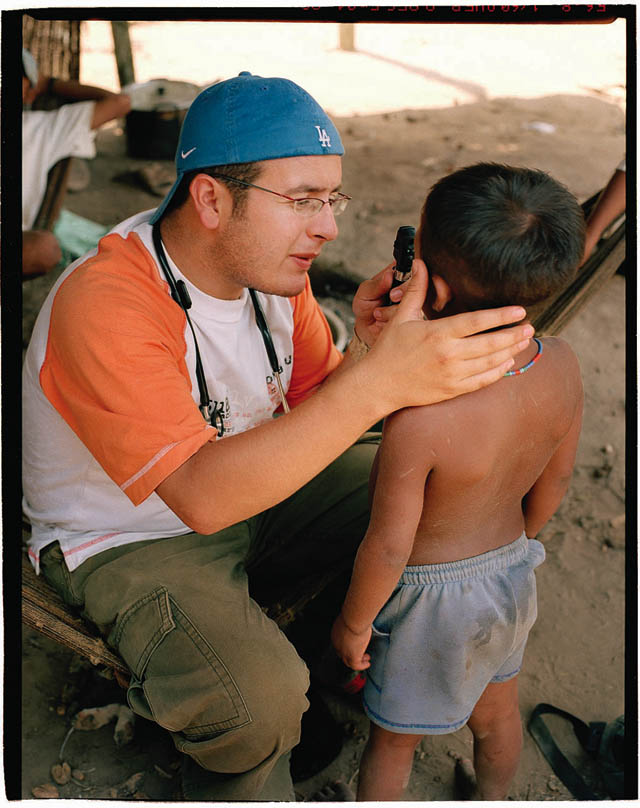

here with Doctor Javier Maldonado, a general practitioner who arrived here to

do an internship, and was so appalled by the living conditions that he

decided to do something about it. He now gives basic medical care to Nukak

Maku groups that have been arriving to this area over the last three years.

As he introduces me to the various clan members, he starts telling me their sad

story. ‘Less

than fifty years ago the first colonists arrived to this area, driven here by

violence in other parts of the country. In those times, people hunted Indians

for sport, or caught them to use as slaves. So it is not surprising that the

nomads of the Nukak Maku preferred to stay in the jungle where nobody

bothered them. And then one day, about seventeen years ago, a group of around

fifty sick and starving women and children came running into the village of

Calamar, after a journey of two hundred kilometers on foot. What had happened

to the men of this group never became clear. Naked and hungry they entered

the gardens and houses of the locals, looking for food. Being nomads, they

had no concept of private property, and communication with them was

impossible because nobody could speak their language. The locals were dead

scared of the naked ‘savages’ and sent them back into the woods as quickly as

they could. But “the evil” had happened – this brief contact with Westerners

had brought them in contact with influenza and tuberculosis. Within a few

years the majority of the Nukak Maku were dead.’ Just as I am convinced

that I am really in the sixteenth century, a noisy Black Hawk helicopter

flies low over the camp. These choppers are part of the United States’ arsenal

in the ‘War on Drugs’; they are used to protect fumigation planes spraying

coca crops. But, put quite simply, it’s not working. At least not in this region.

Here in the rainforest no other crop will grow except for bananas and

potatoes, both of which can be produced far cheaper in other parts of the

country that have better transport infrastructure. And as long as there is

demand for cocaine, there will be coca plantations to supply. A more recent

problem for the area is the discovery of underground oil reserves – an

estimated 24 billion barrels - which makes the area attractive to both the

illegal armed groups that have been waging war in the country for several decades.

These two groups – the FARC Guerilla and the AUC paramilitaries - control

just about everything that is illegal in Colombia – from massacres to

kidnapping to the cocaine trade. Javier:

‘After the first contact the Nukak Maku were world news for a couple of

days. They were the last group of Indians to come in contact with the Western

world. UNESCO put the Nukak Maku on their list of ‘human groups that need

special treatment’ because of their high vulnerability. But after that they

were largely abandoned. The government designated an area of a million

hectares as a ‘resguardo’, a reservation where they were supposed to be able

to live in peace. However this reservation appeared to be a fiction; parts of

the assigned area had already been colonized and were being used as farmland,

mainly for coca plantations. In

recent years the area has increasingly become a war zone in which the AUC and

the FARC battle over territory. They do not care about indigenous’ rights;

there have even been cases where they were captured as slaves to serve in

their army units.’

Javier:

‘At the time of their “discovery”, the Nukak Maku’s population was

estimated to be about 1500. At present, about 380 are thought to be alive, of

whom the eldest are around 40 years old. Over the last 15 years all the

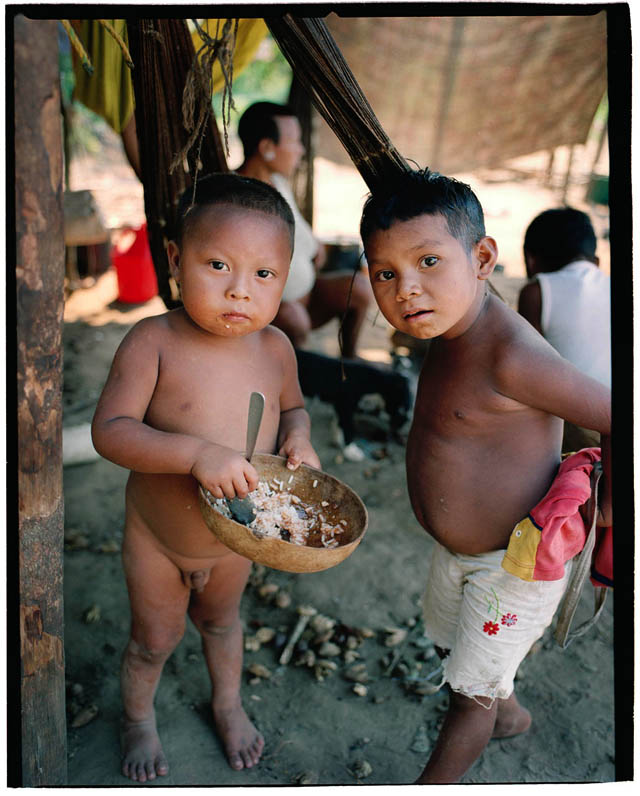

elders have died, mainly from flu and killing. Of these 380 persons, over 40%

are now living in refugee camps like this one, on land with a very different

vegetation to what they are used to, making it almost impossible for them to

feed themselves. Also, it is impossible for them to move around in this area.

Usually the Nukak Maku ‘move’ every 3 to 10 days, but the first refugees

arrived here over 3 years ago and have not been able to change location once.

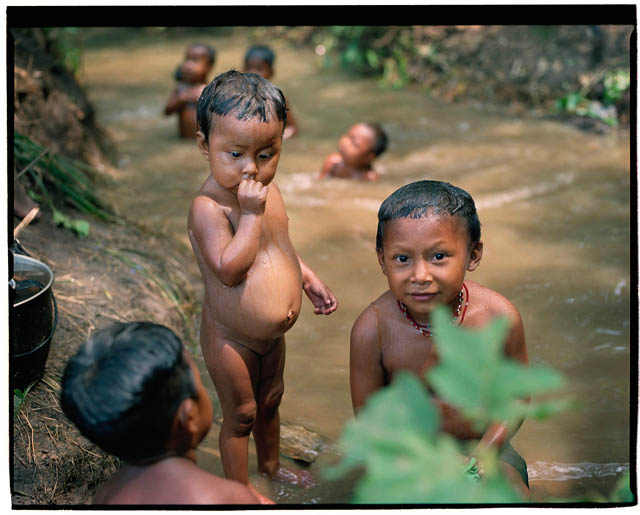

The piece of land they have been allocated does not have flowing water; instead

they use two nearby ponds – one for drinking, one for bathing. This is why

all children have parasite-infections. But the problem is worsening; the drinking

water pond has dried out, and the washing water basin is too dirty to be

drunk. The rainy season probably won’t start for 2 months. Even

among the extremely friendly and positive Nukak families, hunger and thirst

are starting to cause rifts; last night there was a fight, and this morning

two families left the camp, looking for a better place to live. That will not

be easy as the entire surroundings of San José de Guaviare are colonized; the

farmers do not tolerate Indians on their land, and nobody will offer them an

airplane ride back to their territory. Private

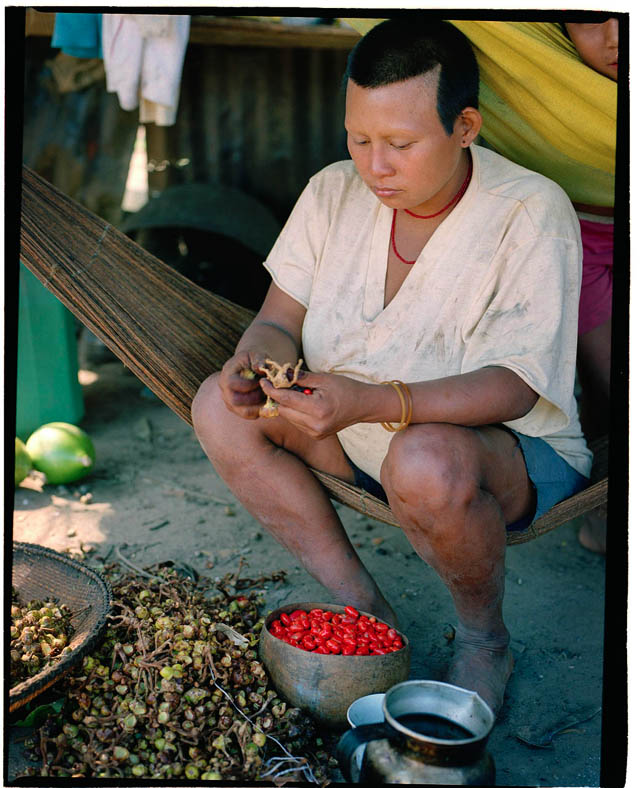

property and money are not concepts the Nukak Maku traditionally understood.

The survival of the Nukak is based on moving frequently from site to site,

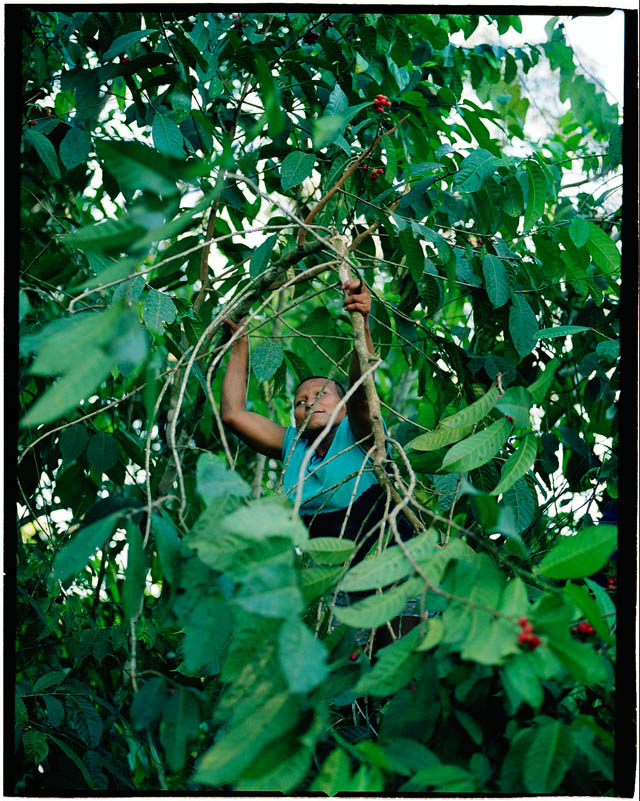

using the few products the rain forest offers for survival. When they discover a tree with

berries, or a palm tree that has edible maggots in its bark, they tear it

down immediately. They leave the seeds on the ground so that when they come

back to the same site, new trees will have grown. When they arrived here they

did the same thing on farms, but to the farmers the palm trees are a status

symbol. As a consequence the farmers do not hesitate to shoot when the

Indians set foot on their lands.’ When he hears I am from

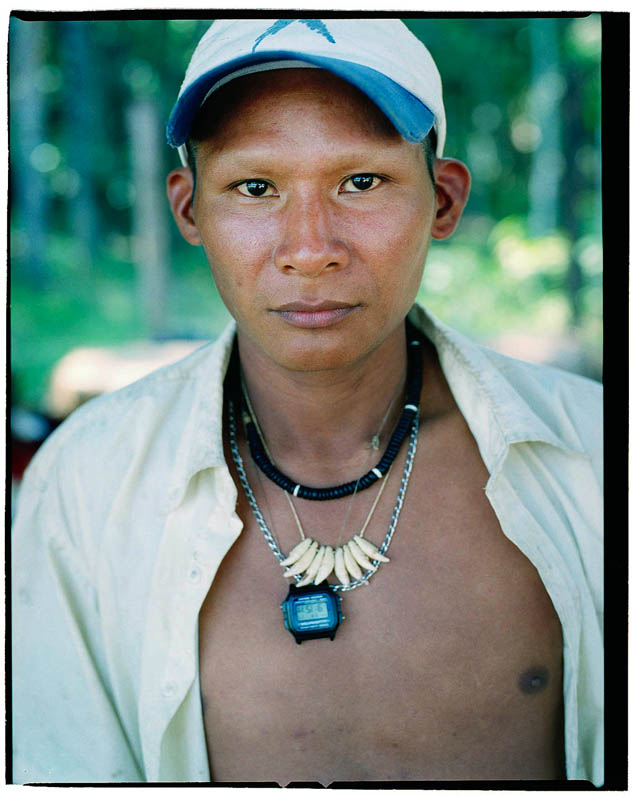

Bogotá, one of the older members of the group approaches me. He introduces

himself as Hweby. I estimate he’s

about 35 years old. In poor Spanish he asks me whether I can tell him where

his son is. He was transferred from the local hospital three months ago with

tuberculosis. They

said he would be transferred to Bogotá. Since then the family has had no news

of him. As I live in Bogotá, Hweby asks me whether I have seen him. Whether

he is doing well? Whether he is still

alive? Explaining to him that Bogotá has 11 million inhabitants is useless. His

culture does not have numbers: no ages; no distance; and no money. He can’t

relate to a society where everything is counted in quantities. General

practitioner Javier says that the only good news he can give Hweby is that

the local hospital

would have given him notice if his son had died. But even he can’t get any

more information - an indigenous child is not high priority.

Javier

continues his story. Over a year ago he teamed up with Jorge Restrepo, an

anthropologist who has had contact with clans since 1989 and has lived in the

jungle with a clan of Nukak for over a month. Together they are trying to bring

the clans’ plight to Colombia’s attention as well as to international aid

organizations. ‘This is harder than

you might expect – even the urgent installation of a manual water pump

(costing US$150) has so far been impossible. The Red Cross recognizes there is a serious problem, and said they would

send someone to evaluate the situation. Nobody ever arrived. The government’s

department of public defense sent an observer to this

very same refugee camp, where people have been living for 8 to 14 months. When

the observer asked the Nukak whether they were going to live here permanently

or whether they were planning to leave. The Nukak answered that they were

‘just passing through”. As a result, the observer concluded that they did not

qualify for

refugee status or funding as they were still nomadic. Ironically, the

Nukak Maku are not poor monetarily. Since 1996, the Colombian government has

put aside a yearly budget to help various indigenous groups, including Nukak

Maku. By now this fund is in

the order of US$200.000. However, owing to a bureaucratic technicality, they

are unable to access their share:the Nukak do not have

a leader, which means nobody can claim this money on their behalf. For a

couple of months the government has been paying various Nukak families US$150 per month to

survive on. However, as a nomadic tribe, they have no concept of money

management. They go the supermarket in the city, spend 150 dollars on food

and drinks, eat and drink all they can for 3 days, and then have nothing left for the

rest of the month.’ We

are ready to call it a day. I can go back to an air-conditioned hotel room

and a hot meal. The 20x50 meter piece of land, granted to this group of about

70, is situated 12 km from San José city. Owing to a military curfew, we have

to be back in the village before 6pm. On our way, we pass a huge infantry

army base as well as a big antinarcotics army base. That

night I discuss the Nukak Maku with Jorge Restrepo, the anthropologist who

first encountered them 17 years

ago. ‘It is not entirely

true that the Nukak Maku had their first contact with the Western world in

1988. After they arrived at the village, they were returned to the Amazon

where other groups of nomadic ‘Maku’ live. But they could not communicate

with those

tribes either; the languages were completely unrelated. Suddenly, a most

unexpected reaction came from the New Tribes Mission (NTM), a fundamentalist

US missionary organization, infamous for their aggressive methods of

conversion and banned from most Latin

American countries. The NTM appeared to have had a secret mission post in the

Nukak Maku territory for years. They had studied the language extensively and

several of their missionaries could speak it. With their help the question of

the Nukak Maku’s

origin was quickly solved, and they were returned to where they came from.

Shortly afterwards the government sent me to the mission post to study the

Nukak. It was a strange experience - flying over an endless, dense jungle,

and suddenly there was this hole,

a landing strip that the missionaries had built! Even though the New Tribe

Missionaries allowed me into their camp (under obligation), they made it

difficult. The first contact with the groups of Nukak that passed the mission

post for food and medicine

was friendly, but after that they became suspicious and even aggressive

towards me, up to the point where I was afraid they would try to kill me with

one of their poison arrows. It turned out that the missionaries had scared

the Nukak saying things like: ‘We

do not know what that man carries in his heart’. Finally, I became so

desperate that I actually wanted to leave. But they told me this was

impossible; it would be about 3 more months before the next plane would

arrive. Out of desperation I just started

following a group as they made their way out of the mission post. Within 15

minutes there was no way I would ever find my way back by myself. For a

Westerner, there is no way to find food in the rainforest, so when the Nukak

knew I was following them, they

also knew leaving me behind would be my death. I told them that I wanted to

earn my right to stay with them, that I did not want to be a burden, but as I

had absolutely no ability that was of value to them, they named me their

‘Maku’ (slave). I became the

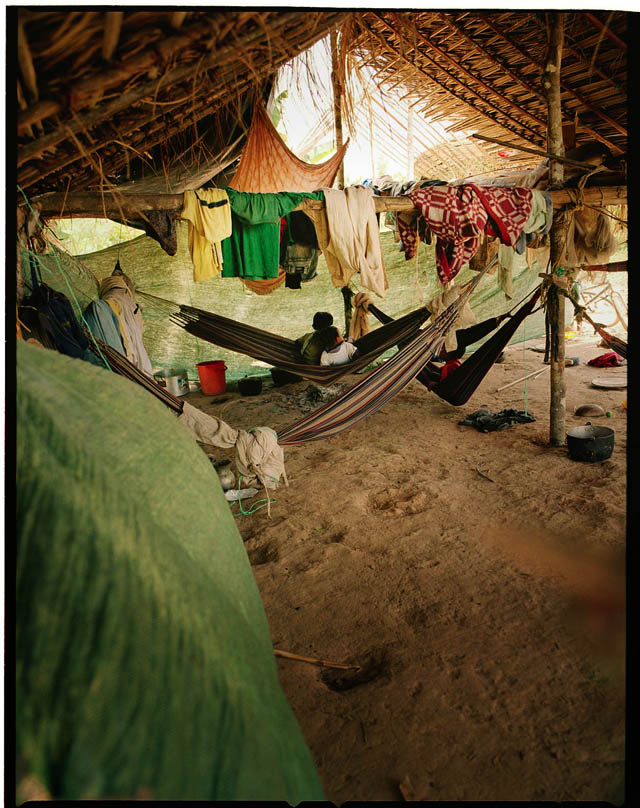

“slave of the slaves”. Every night I had to

find wood to keep the campfires of 5 families going for the night. The nights

with the Nukak Maku were the most special experiences of my life. When they

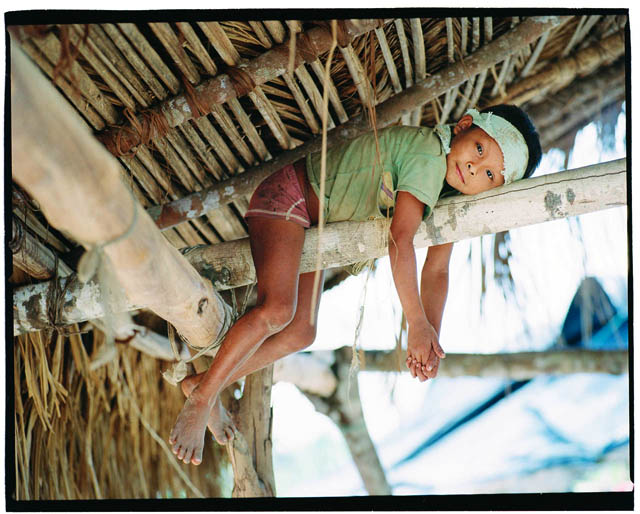

set up camp, within 5 minutes every family builds a hut of branches and banana leaves. With a

kind of twine they get from a plant, hammocks are made which are placed in a

triangle around a fire. As the nights in the jungle are quite cold and

everybody is naked, every time the fire starts going out someone wakes up and adds more

wood. Usually someone else wakes up, tells a story, and the entire clan

bursts out laughing again. Even better are the times when they happen to meet

another clan of Nukak Maku in the jungle. Stories are told and the groups

party for days

on end.’ The

next day we travel 12 kilometers in the opposite direction, along the border

of the Guaviare River. Again we pass a huge military base, this time

belonging to the Government commandos. The army base bears the name ‘Nukak’,

and I remember Jorge

telling me that he and other anthropologists have been protesting about this

to the government for years, without success. According to International Law,

army installations are not allowed to carry names belonging to parts of the

civil population as this

can put those people in danger. So, whilst the Nukak want no part in the

Colombian armed conflict, both paramilitaries and guerilla groups now

associate their tribal name with army commandos, instead of with the peaceful

indigenous people they are. To

make matters worse, the government placed the base partially in territory

that had been assigned to a different group of displaced nomadic Indians, the

Guayaberos. They arrived here 2 years

ago with about 180 families who had been violently forced from their own territory.

Currently, the Guayaberos also have to share this area with about 80

displaced families of Nukak Maku that have nowhere else to go.

After

meeting one of the Guayabero-clans, we continue to the very first Nukak Maku

refugees, which have been away from their reservation for over 3 years, and

who have lived in the Guayabero

refugee camp since then. They

all speak good Spanish, ride bicycles, and have a wind-powered water pump.

One of the mothers even has long hair. Suddenly we hear someone cursing in

Colombian slang. ‘Holy shit, how my

feet smell! - Those fucking rubber boots!’ One of the women

calls: ‘Hey, Mauricio, want a cup of coffee?’ He answers that he does not

feel like drinking coffee but would

prefer guarapo (an indigenous

alcoholic drink made of fermented fruit, in this case pineapple). [Following

introductions,

he tells me how he fled from the hands of the FARC, who forcibly recruited

him into their army. He now works on a coca plantation in order to provide

for his clan. But the clan is expanding just a little too quickly, with over

100 people on a piece of

land not even half the size of a football field. Of course, he would prefer

to return to his tribal lands and lifestyle, but that is becoming more and

more difficult. “We

like comfort as much as you white people do. So, for example, I would like to

take at least

a metal machete with me into the

jungle. And maybe a bike,” he adds, laughing out loud. Javier: ‘With the passing of

time, of course, it will be harder and harder for the displaced indigenous

groups to return to a nomadic lifestyle. The children that were born here will have a very hard

time surviving in the jungle. Besides, they are already facing ‘Western’

problems: they hardly move, which causes many to become too fat to be able to

move swiftly through the jungle. They also eat sugar now, which causes tooth

cavities. Meanwhile they want to listen to pop songs on the transistor radio

that a friend of mine gave them. They now constantly need batteries. The

longer it takes for them to return, the slimmer the chances that they will

actually be able

to do so. Maybe they are best off if they start going to school, speak

Spanish and learn math…’ Two

days later, after a day of exploring the neighborhood and sighting grey and

pink river dolphins as well as coca plantations and cocaine processing

laboratories

near the Guayabero River, we go back to the first

camp we visited. Javier introduces me to Monicaro and his wife and

three children. Monicaro invites us to go

hunting with them. There is no more face painting, and they now keep their

western clothes

on so as not to offend the locals. Besides, they have been wearing clothes

now for almost a year and a half, and already it feels uncomfortable to walk

around naked. Also they are not as resistant to the mosquitoes as before. The

Nukak Maku live off fruits

and berries that they find in the tropical forest, they hunt monkeys and

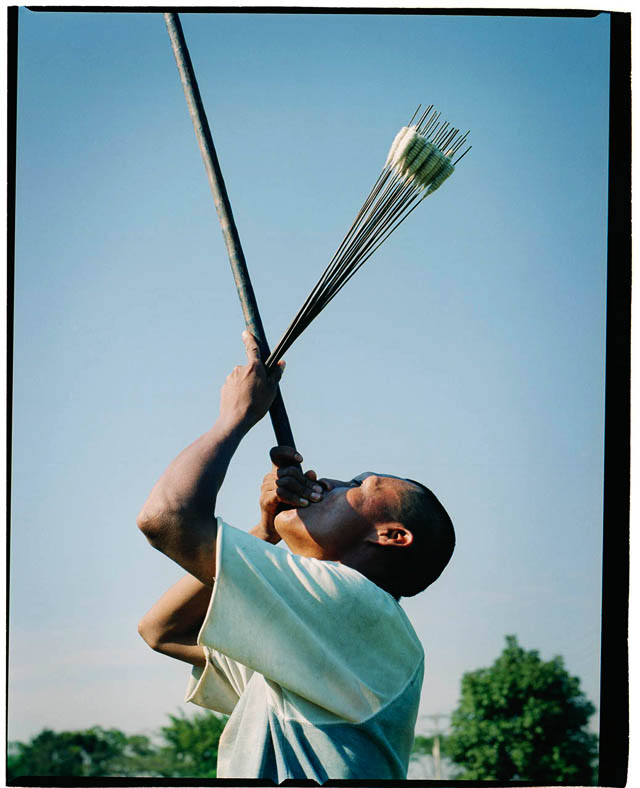

birds, or fish when nothing else is available. Monicaro carries a long bamboo

rod, from which he can blow poisoned arrows that paralyze monkeys and birds

that are in the high foliage

of the rainforest. If they capture a mother monkey or a bird with young, they

also take the offspring to raise them in their camp, releasing them back into

the jungle when they are old enough. The

problem is that around the refugee camp area, the kind of monkey they

usually hunt hardly exists. Instead, they hunt a much smaller kind of monkey,

which has little meat. Furthermore, there are fewer and fewer monkeys, as the

Nukak overhunt the supply in their limited hunting region. It’s

an hilarious sight -

Monicaro the Nukak Indian, riding a kids’ bike on his way to the local jungle

with a bamboo hunting stick. His wife and kids follow, picking berries along

the way. Along the road there are two big dogs guarding a farm. The bike is

hidden in the woods, and

the family crosses a fence to make their way through the meadows. Because we

white people are too slow and noisy and scare the monkeys away before we even

get close, we decide to leave the family alone so they can eat that day. When

we get back to the camp,

it turns out the other family who had left owing to the previous night’s

dispute has also returned. There was nowhere they could go. Hweby, the father

of the sick boy who was sent to Bogota, has fallen ill himself. He has

visited the local hospital twice

over the past week, and they kept him waiting there all day without even

looking at him. Javier examines him, and is afraid he might have

tuberculosis. The doctor’s fear causes a weak smile on Hweby’s face. He

wonders whether, if they send him to Bogotá

as well, he might finally be reunited with his missing son. |